| Frontiers | 您所在的位置:网站首页 › virtual environments › Frontiers |

Frontiers

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Virtual Real., 09 May 2023Sec. Virtual Reality and Human Behaviour

Volume 4 - 2023 |

https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2023.1048812

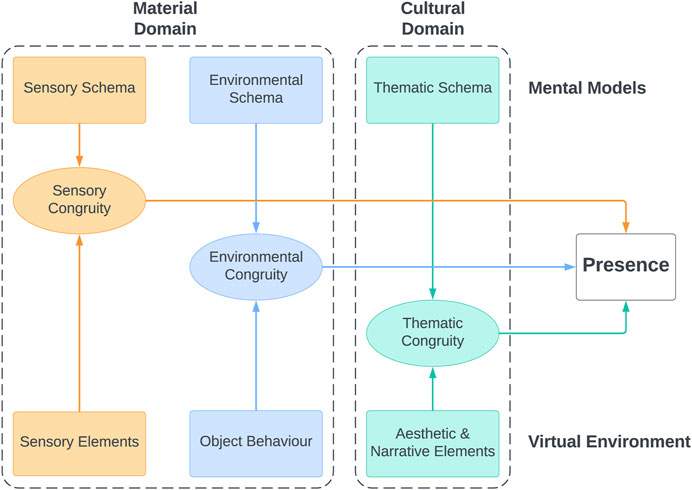

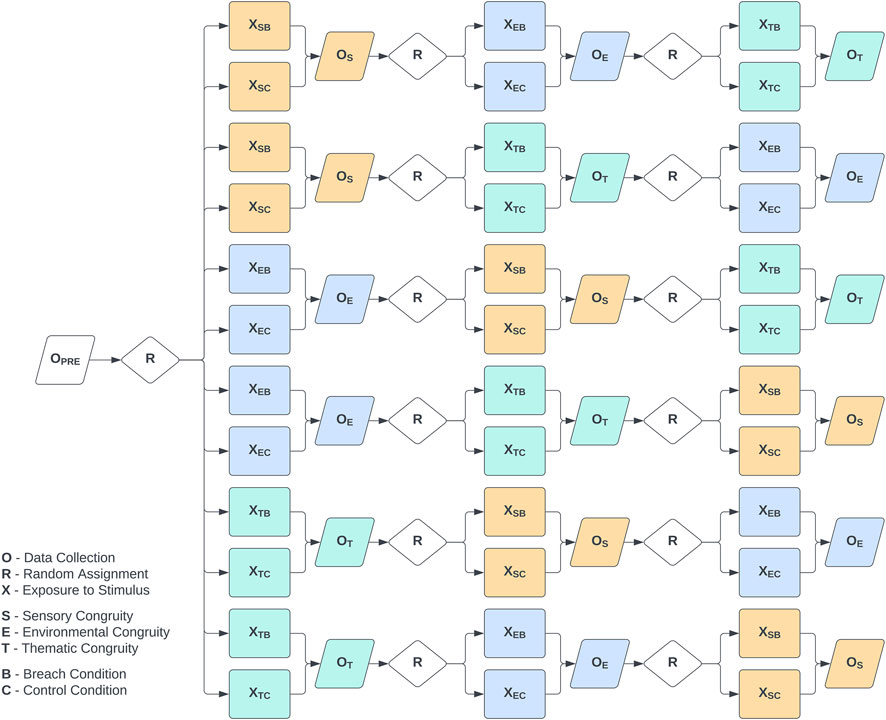

Effects of congruity on the state of user presence in virtual environments: Results from a breaching experiment Tiernan J. Cahill* and Tiernan J. Cahill* and  James J. CummingsDivision of Emerging Media Studies, College of Communication, Boston University, Boston, MA, United States James J. CummingsDivision of Emerging Media Studies, College of Communication, Boston University, Boston, MA, United StatesThe present study investigates how the user state of presence is affected by contingencies in the design of virtual environments. The theoretical framework of congruity is herein explicated, which builds upon the concept of plausibility illusion as one of the essential prerequisites for presence, and which systematically explains and predicts presence in terms of alignment between schemata in the user’s memory and stimuli presented within the virtual environment. Three dimensions of congruity are explicated and discussed: sensory, environmental, and thematic. A series of breaching experiments were conducted in a virtual environment testing the effects of each dimension of incongruity on presence. These experiments were inconclusive regarding the effects of sensory and environmental congruity; however, the results strongly suggest that the state of presence is contingent upon thematic congruity in virtual environments. This finding has theoretical significance insofar as it points towards the necessity of considering genre and cultural context in predicting user states in virtual environments. The study also has practical relevance to designers and developers of content for virtual reality in that it identifies a critical psychological consideration for the user experience that is absent from existing models. 1 IntroductionTechnological advances and decreases in production costs have made virtual reality (VR) accessible to consumers in recent years. However, the technology has remained in a transitional phase, mainly due to a dearth of compelling content (Ismail, 2017; Dickson, 2018). Despite significant market growth driven in part by lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic (O'Kane, 2020), analysts have remained skeptical of the potential for the widespread adoption and integration of VR into everyday life (Ovide, 2022). Despite financial losses, large technology companies, such as Google, Meta, Microsoft, Apple, and Sony, have invested heavily in developing mainstream VR platforms (Amenabar, 2022). Current projections estimate that the augmented and virtual reality market will continue to grow to $36 billion by 2025, with 50 million headsets shipped annually by 2026 (International Data Corporation, 2021; International Data Corporation, 2022). The defining technological affordance of VR is the potential to generate in its users a sense of presence—that is, of being transported from the physical environment to a simulated environment (Bowman and McMahan, 2007). Spatial presence has been conceptualized as “a psychological [user] state in which virtual … physical objects are experienced as actual physical objects in either sensory or non-sensory ways” (Vorderer et al., 2004). Even before the successful commercialization of VR, there have been extensive empirical investigations of the effects on presence associated with various platform affordances, including degrees of freedom, latency, display resolution, and field of view (Cummings and Bailenson, 2016). However, hardware is only one component in the creation of compelling experiences: Careful attention must also be paid to software and content design, including interactive systems, user interface elements, and the construction of the simulated space to successfully generate a feeling of presence in users. While it is often assumed that sensory fidelity is the primary factor in the immersion1 afforded by VR systems—which in turn allows for feelings of presence—past research on the content of virtual environments (VEs) has demonstrated that this is not always the case: Affective narrative and visual cues embedded in the environment have been associated with higher self-reported levels of engagement, naturalism, believability, and reality compared to an affectively-neutral environment represented with the same level of fidelity (Baños et al., 2004). Riva et al. (2007) altered lighting and background sounds in a virtual park to induce emotions of relaxation and anxiety and found that even when presented with the same arrangement of virtual objects, participants reported a greater sense of presence in the affectively-valenced parks than in an affectively neutral control condition. These effects have also been related to the pre-existing psychological dispositions of the user, such that arachnophobes report higher levels of presence when exposed to a virtual spider, and ophidiophobes report higher levels of presence when deceived by an experimenter to believe that a VE contained unseen snakes (Renaud et al., 2002; Bouchard et al., 2008). We propose that in addition to the influence of affective cues, feelings of presence are also partially determined by content features of the VE that affect cognitive processing. In this, we draw from Slater’s (2009) concept of plausibility illusion, defined as the sense that “what is apparently happening is really happening” (3553). In contrast to place illusion, Slater relates plausibility illusion to the realistic behaviour of virtual objects and agents rather than the fidelity of their representation. Supporting this perspective, Slater (2009) found that not only was presence affected by the presence or absence of shadows but by the degree to which the movement of shadows tracked with the virtual objects that cast them. This observation suggests that evaluations of plausibility in a VE are related to normative expectations regarding the behaviour of objects, and the interactions between objects and their environment. Such expectations are presumably drawn from past experiences outside of a VE; originating from the user’s day-to-day existence in physical reality, these expectations may appear childishly obvious, even axiomatic (e.g., when I move my hand, the shadow of my hand also moves). Indeed, Piaget (1930) argued that associations between sensory cues were formed and internalized in childhood, as once-novel observations about the world crystallized into causal belief systems. The child thus forms mental models, or schemata, that associate physical objects perceived in reality with patterns of anticipated behaviour. Individuals’ understanding and expectation of the behaviour of objects in physical space has been theorized as fundamentally schematic: Judgements that might be considered common-sense, such as whether an object on the edge of a table might be expected to fall, rely on quasi-probabilistic, heuristic models of Newtonian physics under familiar conditions. Such models allow humans to make predictions about the physical world at an intuitive level (Battaglia et al., 2013). The necessity for happenings in a VE to “unfold according to the knowledge and prior expectations of the participant” has been recognized in past research as one of the prerequisites for maintaining the credibility of the simulated scenario, and thus, plausibility illusion (Rovira et al., 2009, 3). One of the most exciting possibilities for the design of VEs is immersion in spaces unbound by physical constraints. However, the potential for the behaviour of the perceived environment to diverge from schematic expectations poses problems on both a theoretical and design level: One might expect any such breaches to critically undermine the plausibility illusion, resulting in a disruption of the user’s sense of presence. Nevertheless, the fact that immersive VEs are possible at all, despite operating under a variety of physical and technological constraints (e.g., bounded space for movement, the absence of olfactory sensation, limited range of haptic feedback) illustrates that there is some psychological tolerance for differences in the processing of physical and virtual realities. Congruity describes the alignment of two sets of sensory cues in a VE with a schema prescribing their interaction (Cahill, 2018). In this theoretical framework, schemata are internalized, normative, organizing heuristics that articulate expectations for how objects in the world should behave based on past observations. The present study explores the extent to which various types of schematic understandings govern the cognitive processing of VEs. Cahill proposes three dimensions of congruity as potentially influential for the experience of presence in VEs: sensory, environmental, and thematic. Each dimension is briefly explicated below, and relevant hypotheses are proposed for each (see also Figure 1). FIGURE 1 FIGURE 1. Conceptual diagram of the theoretical framework. In physical reality, objects are perceived simultaneously through different sensory modalities, and the relationships between these various sensory cues are generally stable. While there may be limitations on the modalities of sensation that may come into play in a given circumstance—we cannot feel all of the objects that we can see, for instance—in those cases where multimodal cues for a single object are available, there is likely to be a schematic association between them. For example, if one sees a waterfall in the distance, one does not necessarily expect to be able to perceive it through their other senses. However, moving closer, one has definite expectations regarding what the waterfall will sound like when it becomes audible and what it will feel like when it becomes tangible. It is important to note that incongruity between sensory cues is very different from the absence of sensory cues in a VE. As observed above, there appears to be a certain level of tolerance for missing sensory information in mediated contexts, to the extent that participants have been observed to “fill in” haptic sensation in experimental contexts where suitable visual cues (e.g., a handle attached to a coiled spring) are given (Biocca et al., 2001). If anything, this observation is consistent with the theory that certain sensory cues are associated in cognitive processing, yet it does not indicate how contradictory cues are processed. Physical objects in physical reality are also governed by physical laws. Individuals develop heuristic understandings of these laws through experience, resulting in intuitive mental models that approximate principles of physics (Battaglia et al., 2013). The behaviour of virtual objects is expected to conform to these schematic models: This expectation is already implicitly acknowledged in the engineering of game engines and other software systems that underpin virtual reality, which typically include the ability to simulate the physics of virtual reality as a baseline affordance. Environmental congruity articulates this principle and the extent to which the behaviour of virtual objects aligns with the relevant schema for the behaviour of a comparable physical object. In most cases, environmental congruity is operationally relevant to virtual objects’ motion or collision, since the simulation of other physical properties (e.g., temperature, viscosity, mass) requires sensory affordances that are less readily available with commercial VR hardware. A notable caveat regarding environmental schemata is that they may be context-specific to some degree and that the relevant contexts may extend beyond those with which an individual has direct experience. A schema articulating the behaviour of physical objects in high orbit or on the Moon will no doubt differ from one articulating the behaviour of a comparable object on Earth and yet may be as deeply internalized through educational or mediated representations of those contexts. Thus, if a VE can maintain the plausibility illusion of being on the surface of the Moon, environmental congruity may be more readily maintained through simulation of low-gravity physics than through a recreation of familiar object behaviours. The contextual associations of different environmental cues and the objects in those environments are addressed by the concept of theme or the understanding that certain classes of objects are schematically associated with one another and with particular environments. While the basis for thematic associations may originate in personal experience, the prevalence of genre as a formal feature of entertainment media suggests the possibility that thematic expectations are likely to be culturally determined and based on other mediated experiences. While genre is often thought of as inherent in texts, it can also be functionally conceptualized in terms of cognitive structures that the text invokes in the reader (Schmidt, 1987). This way of thinking is in line with Livingstone’s dual conceptualizations of genre as both specifying a worldview common to the mediated and physical worlds and embodying a “contract” to be negotiated between the text and the reader (Livingstone, 1993; Livingstone, 2013). Arsenault (2009) has discussed the complications inherent in attempting to rigidly define genre typologies for interactive media objects such as video games. Rather than objectively defined categories, genres may be thought of as dynamic arrangements of narrative structures and aesthetic elements that arise from historical trends of cultural influence involving individuals as consumers, arrangers, and producers of media. The encoding of consumed media into mental models is thus implicated in the reproduction of genre on a cultural scale, as designers draw on their own memories of mediated experiences to shape the form and content of new VEs. From this perspective, an experience falls into a particular genre classification not because of any stable, deterministic traits but because of the agglomeration and interaction of sensory and narrative cues associated by the audience with a particular schema. Elements that are strongly associated with particular genre classifications or thematic schemata are hypothesized to invoke thematic incongruity when they appear out of their familiar context, even where this appearance does not produce incongruity along the other two dimensions: As an example, the image of a stagecoach, pulled along by horses, and accompanied by the appropriate sounds of rattling and whinnying, may be sensorially and environmentally congruous, and will not arouse dissonance in an environment that is coded as “Western” (e.g., a dusty road or mountain pass). The same sensory cues, however, will become uncanny if placed in the environmental context of a modern-day city street or accompanied by the trappings of a futuristic science-fiction narrative. The inclusion of thematic schemata, based on experience of culturally embedded narrative and aesthetic cues—alongside sensory and environmental schemata derived from the experience of physical reality—represents one of the primary theoretical contributions of the congruity framework proposed by Cahill (2018), as compared to models similarly oriented towards predicting the experience of presence by users of immersive technology. While this model is consistent with past empirical work (see Renaud et al., 2002; Baños et al., 2004; Riva et al., 2007; Bouchard et al., 2008; Slater. 2009; Skarbez et al., 2017), there have been no studies to date that take a confirmatory approach to congruity, and thus, there is a clear need for experimental research in this area. As with other normative schemata (e.g., social norms), individuals’ past experiences in the material and cultural domains are presumed to be de facto congruous, and thus, the operation and significance of congruity in VEs is most easily demonstrated through breaching experiments, with manipulations that create circumstances of incongruity for the participant. In testing the following hypotheses, derived from the theoretical framework of congruity, the present study addresses the need for empirical testing of the framework in general and of the effects of thematic congruity in particular: H1a: Spatial presence will be lessened when spatial congruity is breached. H1b: Spatial presence will be lessened when environmental congruity is breached. H1c: Spatial presence will be lessened when thematic congruity is breached. H2a: Symptoms of simulator sickness will be intensified when spatial congruity is breached. H2b: Symptoms of simulator sickness will be intensified when environmental congruity is breached. H2c: Symptoms of simulator sickness will be intensified when thematic congruity is breached. RQ1: Are the effects of breaches along certain dimensions of congruity more disruptive to spatial presence than others? 2 Materials and methods2.1 SampleParticipants were recruited from a pool of students enrolled at a large urban research university in the northeastern United States (N=138). Recruitment materials were posted to an internal web interface accessible to students enrolled in classes that made them eligible to receive academic credit for research participation. Additionally, flyers were placed around the university campus to recruit participants who were not enrolled in eligible courses, who could instead opt to receive a gift card as compensation. All recruitment materials and study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university where the study was conducted. The only inclusion criterion was that participants were required to be at least 18 years of age. The median age of participants was 21 (IQR=3), and the sample included 117 female and 20 male participants, as well as one participant who declined to report their gender. 2.2 ApparatusParticipants wore an Oculus Rift S head-mounted display (HMD) and held a single Oculus Touch motion controller in their dominant hand. This HMD has a visual resolution of 2,560 × 1,440 pixels and a refresh rate of 80 Hz. Head movement is detected using an inside-out tracking system with five cameras supporting six degrees of freedom. Audio is provided using integrated above-ear speakers in a stereo configuration. This model of HMD was selected based on its compatibility with and similarity to other hardware adopted by consumers at the time the study was conducted (Cummings et al., 2022). While this device must be connected to a PC via a cable, this allows for greater graphical fidelity and tracking performance in contrast with comparable fully wireless HMDs such as the Oculus Quest (Martindale, 2020), with limited impact on participants’ range of movement given the demands of the study and available space. A researcher checked the fit and positioning of the HMD prior to beginning the experiment. A cable suspension system allowed total freedom of movement within the designated space, and a researcher always observed each participant, ensuring their safety. 2.3 StimuliA VE was developed using the Unity game engine, combining commercially available and custom 3D models and texture assets. The environment used for all experimental stimuli (detailed below) was modelled on a medieval great hall and was designed to be open and expansive (see Figure 2). This environment was also intended to evoke schemata associated with history and fantasy genres through distinctive architectural features and decorative design elements (e.g., gothic arches and stained-glass windows). These cues would serve as reference points for stimuli situated within the environment as part of the experimental manipulation of thematic congruity. Each stimulus was designed to address a different dimension of congruity, appearing in either a breach (treatment) or congruous (control) condition, as described below. Each stimulus was preceded by a simple task instruction for the participant, encouraging them to maintain attentional focus. All instructions to participants and questionnaire materials were displayed within a separate, content-neutral environment (described below) to avoid interfering with the participant’s perceptions of the experimental environment. FIGURE 2 FIGURE 2. Screenshot of the experimental virtual environment, created with Unity. 2.3.1 Sensory congruity stimulusParticipants were instructed to observe a series of balls that would be released above the top of a sloped table and to attempt to predict where the balls would roll (see Supplementary Figure S1). Both the balls and the table were rendered with a woodgrain texture, intended to invoke audiovisual sensory schemata when the objects were observed to come into contact (i.e., when each ball struck the top of the table and as it subsequently rolled along the surface). Thus, in the congruous condition, this motion was accompanied by a Foley recording of wooden balls bowled across a wooden surface. Conversely, a Foley clip of water falling over river rocks was substituted in the breach condition to accompany the visual stimulus. 2.3.2 Environmental congruity stimulusParticipants were instructed to observe a book positioned to appear balanced on the edge of a table and attempt to predict the moment when the book would fall (see Supplementary Figure S2). In the congruous condition, the motion of the book object was controlled by a physics engine with parameters consistent with gravity and atmosphere at the Earth’s surface. Thus, after a brief pause, the book would gradually tip over the table’s edge and fall to the floor. In the breach condition, the vector of simulated gravitational force was inverted at an oblique vertical angle, causing the book to “fall” upward and away from the participant and strike the opposing wall. 2.3.3 Thematic congruity stimulusParticipants were instructed to read and attempt to memorize a short passage of text. The passage was an excerpt from The Tempest by William Shakespeare, which could be read in contexts consistent with either a historical or fantasy genre. In the congruous condition, this text was displayed on a piece of parchment laid out on a wooden lectern in front of the participant, in an aesthetic style consistent with other decorative elements in the environment (e.g., bookcases). The text was also rendered in a typeface designed to emulate handwriting while remaining easily legible (see Supplementary Figure S3). In the breach condition, the same text was displayed on a computer terminal with a futuristic aesthetic intended to invoke the science fiction genre and was likewise rendered in a monospace typeface similar to that used in development environments and text-based computer interfaces (see Supplementary Figure S4). 2.4 ProcedureParticipants were informed about the scope and objectives of the study and gave informed consent before the experiment began. After being fitted with an HMD, each participant completed a pre-test questionnaire measuring relevant demographic and psychometric traits using the motion controller. A content-neutral VE was created to allow participants to respond to this and subsequent post-test questionnaire instruments without removing the HMD. This environment consisted of empty white space with a textured plane extending in all directions and containing a flat, floating panel which displayed questionnaire items and with which the participant could interact by pointing and using the buttons on the motion controller. After completing the pre-test procedure, participants were placed in the three experimental stimulus environments described above in random order. For each trial, the participant was randomly assigned to either the breach or congruous condition. Random assignment was independent for each trial so that some participants could have experienced a mixture of the breach and congruous stimuli in different environments, while there was also the potential for some participants to experience only breach or only congruous stimuli throughout all environments (see Figure 3). Following a 60 s exposure to each stimulus, the participant was returned to the neutral environment to complete a post-test questionnaire containing self-reported presence and simulator sickness measures. While these transitions did entail breaking the continuity of the VE, this was thought to be less disruptive than either inserting an incongruous questionnaire interface into the experimental stimulus environment or requiring participants to repeatedly remove and then replace the HMD between each trial. FIGURE 3 FIGURE 3. Diagram of experimental design. Once all three trials were completed, participants were asked to remove the HMD and questioned whether they experienced any issues with the VR equipment. They were then debriefed by a researcher who reiterated the purpose and procedures of the study. 2.5 Measures2.5.1 Immersive tendenciesIndividual differences in the tendency of participants to become involved in immersive media were measured using the Immersive Tendencies Questionnaire (Witmer and Singer, 1998). These differences reflected stable psychometric traits that might influence participants’ perceptions of VEs. This questionnaire instrument consists of 18 items measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale and includes four subscales to reflect aspects of focus, involvement, emotion¸ and jeu (play). Example items include “How good are you at blocking out external distractions when you are involved in something?” (See Supplementary Material, Section 2.1, for the complete instrument.) The separate sub-scales had poor reliability (α.83; α=.81). Vorderer et al. (2004) only report historical reliability for each sub-scale; however, these fell into a range comparable to the reliability of the sub-scales used in the present study (.83≤α≤.93). 2.5.3 Simulator sicknessPotential negative physical symptoms experienced by participants, which have been associated in past research with disruptions in presence, were measured following each trial using an adapted version of the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (Kennedy et al., 1993). This instrument consists of 16 items describing different symptoms of simulator sickness, such as “Fatigue,” “Headache,” and “Nausea.” (See Supplementary Material, Section 2.3, for the complete instrument.) Participants indicated the extent to which they experienced each symptom on a four-point scale, anchored at “None” and “Severe.” Each item was then multiplied by a factor weight and summed according to the three-factor solution provided by Kennedy et al. (1993)2 Given that the SSQ is intended to be an aggregate measure of a variety of different physical symptoms, which are not presumed to co-occur reliably, rather than a measure of latent psychological traits or states, no reliability scores were computed for this measurement. 2.6 Analytic strategyFollowing data collection, self-report questionnaire items were scored and reliability indices for each measure were computed, using the psych package for R (Revelle, 2022). The distributions of dependent variables of interest were then plotted and visually interpreted. In cases where a near-normal distribution was assumed for later analysis, this assumption was confirmed with a Shapiro-Wilk test. The Pearson correlation between self-reported spatial presence and immersive tendencies was then calculated to confirm that—as anticipated—immersive tendencies were a relevant personality covariate for analyses involving spatial presence as a dependent variable. For Hypothesis 1, the assumption of homogeneity of variances was confirmed with Bartlett’s test. A two-sample Student’s t-test was then performed to contrast the self-reported presence in breach and control conditions for each of the three dimensions of congruity. However, given that immersive tendencies had previously been identified as a covariate of interest, a one-way ANCOVA was also performed using the rstatix package (Kassambara, 2022), as the preferred test of these hypotheses. These analyses were conducted using Type II sums of squares, with immersive tendencies entered as an observed covariate. It was anticipated that the distribution of simulator sickness measures would be heavily skewed, given that experiences of mild or isolated symptoms, or where no symptoms are encountered at all, are generally presumed to be far more common than experiences of severe or wide-ranging symptoms (Kennedy et al., 1993). Furthermore, simulator sickness was not significantly correlated with individual differences in immersive tendencies, nor is there any theoretical reason to anticipate such a relationship. For these reasons, the Mann-Whitney U test was used as a non-parametric alternative for testing elements of Hypothesis 2. As part of these analyses, Cliff’s delta was calculated as a measure of effect size using the rcompanion package (Mangiafico, 2022). 3 Results3.1 Effects on presenceAs expected, a weak correlation was observed between individual differences in immersive tendencies and self-reported spatial presence across all conditions (r412=.257,p |

【本文地址】